Fictive Certainties

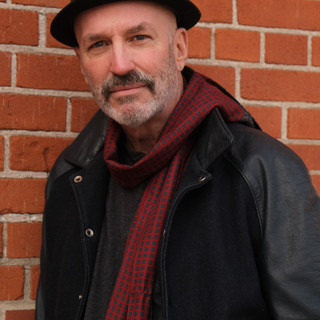

- David Wallace

- Sep 12, 2022

- 6 min read

Platitude: It’s the journey, not the destination.

Given a choice, most folks prefer a parable to a platitude. You must grapple with a parable. There is mystery. Often a mystery that contradicts the surface interpretation. But a platitude is merely tedious. No exegesis required.

I wish I had a parable to offer. But I don’t. I will, however, offer the observation that a journey without a destination is just aimless wandering. And even aimless wandering gets you somewhere. Just because you don’t have a plan doesn’t mean you don’t arrive somewhere.

The word destination appears to contain the word destiny. Maybe not some exultant (or tragic) destiny. But some sort of arrival. Even getting lost and walking off the edge of a cliff provides a destination. Gravity has occasioned all manner of arrivals.

I’ve, essentially, completed my cycling journey. One easy ride to Tsawwasen Ferry Terminal. Less than two hours on the boat. Coast into Victoria. Pack up the bike and mail it home. Then a two hour drive with my brother and his spouse north to Campbell River to see our sister and our mom. Fly home.

What did it all mean?

Had I told myself from the onset that I was setting out on a pilgrimage then maybe my arrival would not feel so... ambivalent. A pilgrimage definitely has a destination —usually a shrine—but it is understood that the journey is a kind of devotion. And the shrine is a reminder that, ultimately, there is only one destination. And everyone arrives there. Eventually.

So, when we say it is the journey and not the destination, aren’t we, in some sense just trying to evade the inevitable? And isn’t privileging the journey over the destination just a way of saying something like carpe diem—seize the day? Or as the proverb advises: Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die?

The choice is not between the journey and the destination. There is no choice. You can’t have one without the other. The choice is (I think) how do we make meaning from all this fuss?

Part of my journey has been spent promoting a novel. A story. One prefaced with a quote from St. Augustine: Faith is to believe what you do not see; the reward of this faith is to see what you believe.

Maybe I do have a parable to offer, after all.

How does Augustine’s definition of faith differ from... well... self delusion? Believing until you see seems like the sort of activity that produces children who avow they witnessed Santa and his reindeer silhouetted against the moon on Christmas Eve. Or naive adults who imagine the face of Jesus burned into a piece of toast. If faith is simply wish fulfillment run amuck then “an imaginary friend in the sky” is an apt description for God.

There is a saying (origin uncertain): We do not see things as they are. We see things as we are. I am guessing most people interpret this something along the lines of: change your attitude and you change the world. Everything depends on one’s perspective. But I think this observation suggests something much deeper.

What if, in some ways, there is no real world. What if there is only a world constructed of our beliefs? Don’t worry, I’m not going to summarize the main tenents of philosophical idealism vs philosophical materialism. Wikipedia can do that.

What I will suggest is that, putting aside ontological questions about the nature of existence, nearly everything of significance in our lives is contingent upon our beliefs. Beliefs we generally accept as self-evident but that are not easily encompassed by the realms of reason and science.

We can advance clever scientific theories about, say, love (an evolutionary adaptation?)—but, ultimately, the explanations feel reductive. They do not reflect our experience of love. Similarly, the argument that free will is simply an illusion—that everything is pre-determined—just feels wrong. And even if we espouses a deterministic world view, we still act as though we have free will. I mean... what is the alternative?

In The Little Brudders of Miséricorde, a character named Spence befriends a talking mouse named Thierry. Spence is loosely based on a real human being (yours truly) but Thierry is entirely invented. Moreover, he is a mouse who talks? In French and English? Thierry may be the less believable character, but I would argue that he is more vivid, more memorable, and more lovable than Spence. Wiser, even. Most readers immediately accept that Thierry is... well... real. At least as real as Spence.

The fictive universe does this all the time. The literary (songs included) and visual arts, in particular, routinely achieve this improbable feat. We laugh, we cry, we grow angry or anxious, feel inspired or defeated—all while watching a Disney animated film where teapots sing and dance.

But, of course, we know that what we are witnessing is not real.

But what of, say, a woman who is deceived by a faithless lover. And though that seems like an example more suited to some medieval ditty, my friend Joan recently told me her story of a lover who used romance and friendship as devices to effect a robbery. She believed he loved her. She was genuinely heartbroken by his deception. Her feelings were real; his were a fiction.

But what if he were not a conman and a cad. What if he were a man, say, who knew he was dying of cancer? And he began a passionate love affair with Joan because Joan was despondent and he wanted to teach her that she is a woman worthy of love. In this scenario, he, himself, has no true feelings of love. He simply wants to do one good deed for someone before he dies.

He is a fraud and nothing he said is true. Yet, after he dies, Joan briefly mourns, but is soon comforted by the man who becomes her life partner and soul mate. In short, the catalyst that revitalizes her was a fiction. A lie.

Hmmm...

In the realm of belief, we generally recoil from the religious fundamentalist who espouses hateful beliefs and whose prejudices are the source of untold suffering. Yet, we may well acknowledge that we know know people-of-faith who live exemplary lives of service to others. Generous, compassionate, accepting persons. Both sorts may be motivated by the same scriptures, the same religious traditions. And, for the atheist, both are motivated by a delusion. The delusion that God exists.

But let’s leave God out of the equation. What of entirely secular people who are full of hateful ideologies? Or guided by compassion and service. Absent a divinity, both sorts have beliefs. From where do these contradictory beliefs arise? I imagine that both attitudes can (and have) been attributed to some sort of evolutionary adaptation. And I’m not arguing that evolutionary biology is false.

But I am arguing that, for example, evolutionary biology is used to effect a system of beliefs. A world view. A culture. Values. It is not fictive, but it plays a fictive role because it narrates a certain kind of story.

And that, I think, brings me to my point. I don’t know for sure why I got on my bicycle and pedalled across much of our vast country. But I feel sure that I will, ultimately, tell myself a story that helps me make meaning of the journey. And that story may well be a sort of delusion. And if it is, it will not be the first time I have deceived myself. And how is self-deception even possible? Who is doing the deceiving and who is taking the bait. Yet I know that I—and likely you, dear reader— we have conned ourselves sometimes. Or, at least, worried that we were deceiving ourselves.

If you have read my novel—any fiction—you have allowed yourself to be beguiled, however briefly. And if your life has ever been profoundly changed by some work of art—you have been beguiled. You may have adopted or adapted your system of beliefs—your values—as a consequence of a fiction. And if you did, then in some ways, you turned a story into scripture by ascribing to it a sort of sacredness. You have set it apart and assigned it unusual importance. A kind of reverence.

All my life I have, in a modest way, been a professional storyteller. I have also read and witnessed stories and been profoundly affected by them. Perhaps, you have too, even if you don’t see storytelling as your profession. And if we cannot understand that we are made of stories, that we fashion our identities with the stories we believe—the ones we know are not true but feel true—if we cannot see that in ourselves...

We are made of stories. Some of those stories may no longer serve us. We may even despise the myths of our childhood. But I don’t think we can carry on without some story that underpins our lives. Perhaps a story that we have so thoroughly integrated that we are no longer even aware that it is source of our being. It was become the air we breath and the lungs that labour even as we sleep.

But if we are not aware that are lives are based on a kind of vital fiction, a guiding myth, a sacred script... If we do not read and reread ourselves and deeply consider our beliefs... If we are unaware that we are, in some sense, imagined though not imaginary...

...then someone else will almost surely capture us in their narrative sweep and we will have not a genuine identity, however fluid it might be over the course of a lifetime. We will be performative creatures—static characters—acting out the roles assigned to us without the awareness that we have been thoroughly authored by someone in need of background characters. We will be the scenery.

And no amount of frantic pedalling will free us.

Congrats on your journey and reaching the destination in one piece. No doubt driving against the wind encouraged reflection and inspiration, which will surface in your future writing endeavors. See you soon.

I don’t know what to write in response to this post, David, except to say that it is deeply moving. I am very happy you reached your destination. Does another journey begin now, one with a new destination? See you soon, back in Montreal. ❤️